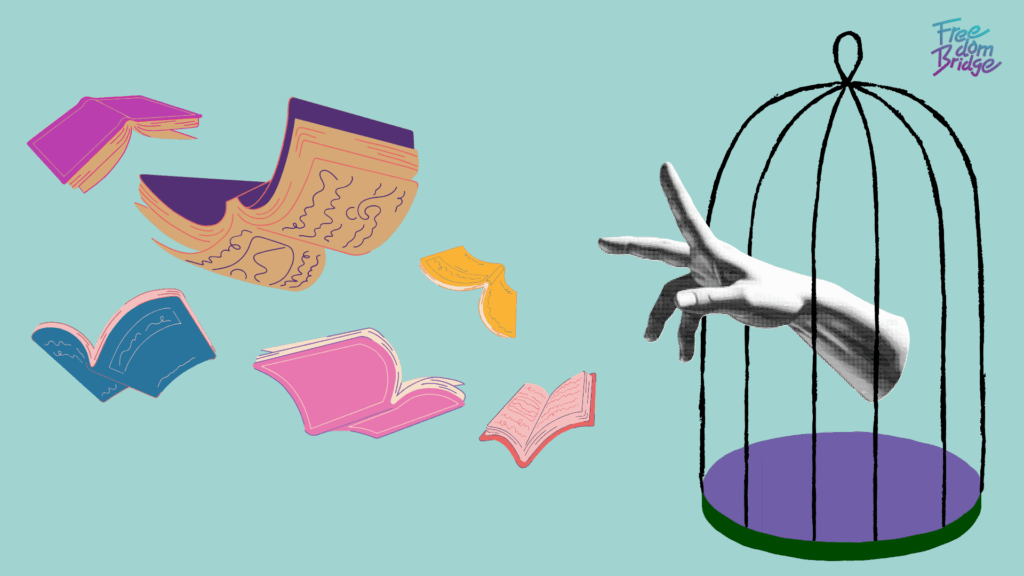

On April 3, 2025 Pol. Col. Tawee Sodsong, Minister of Justice, presided overthe opening ceremonyof the “Read for Release” program at the “Dream Weaving Yard” of TK Park (Thailand Knowledge Park). The initiative was introduced in response to the recognition that some individuals commit offenses due to a lack of knowledge and education. The primary goals of the program are to promote learning opportunities, encourage a reading culture among incarcerated individuals, and support their personal development — helping reduce the likelihood of reoffending after release.

The program represents a positive step toward improving the quality of life for incarcerated individuals and demonstrates that the Department of Corrections recognizes societal challenges and is making efforts to help address them.

However, in practice, many prisons in Thailand are often reluctant to accept donated books due to concerns over the additional workload required for screening and sorting materials. Larger facilities — such as the Bangkok Remand Prison and the Central Women’s Correctional Institution — still accept book donations, but each has its own specific restrictions and limitations.

Book donations restricted to the ten approved visitors

At the Central Women’s Correctional Institution, books can be donated directly at the administration office without filling out any forms.

In contrast, the Bangkok Remand Prison requires donors to complete a donation form, including details about the materials being donated, along with the donor’s full name, address, and a copy of their identification card. Importantly, the donor must be one of the ten individuals authorized to visit a particular prisoner at that facility. Additionally, donated books are sent to the prison’s central library and cannot be designated for a specific unit or a specific inmate. The final decision on sorting and distribution lies solely with prison officials.

However, this requirement is rather contradictory. The Bangkok Remand Prison does allow family members to send books directly to specific inmates by naming the intended recipient. Yet, only those whose names are included among the ten approved visitors are permitted to donate books through this process.

The ten-person visitor list is only the first restriction. Prisons also impose numerous additional rules on book deliveries—many of which are so complex that they are impractical to follow, or even if they can be followed, they fail to function effectively in practice.

Unrealistic book delivery schedules that make access nearly impossible

In addition to the restriction requiring donors to be among the ten approved visitors, the process of sending books to a specific prisoner at the Bangkok Remand Prison is further complicated by a strictly limited delivery schedule. Books can only be submitted during the first ten days of each month, and only between 8:30 AM and 2:30 PM — during the prison’s official working hours. After accounting for weekends and public holidays, in some months there may be as few as six actual days on which books can be delivered.

The restrictions on sending books do not end there. The prison also requires that anyone on the approved visitor list who wishes to send books must attach a copy of their visitor registration document. This effectively means that family members cannot come to the prison solely to submit books; they must also conduct an in-person visit with the inmate on that same occasion. Even though prison staff can already check the system to verify whether a person is on the approved visitor list, the donor is still required to carry out a visit as an additional proof of their relationship to the prisoner.

This becomes a third layer of restriction, on top of those already mentioned. The Bangkok Remand Prison designates visiting days based on the type of criminal case, separating visits into categories such as drug-related offenses and general criminal offenses. As a result, the number of days when family members are actually able to visit an inmate and deliver books can be reduced to as few as three days per month.

When these conditions are taken into account, the policy of accepting books from the 1st to the 10th of each month becomes unrealistic in practice. This is because there are numerous additional and highly complex requirements involved—far beyond simply allowing book deliveries during the first ten days of the month.

Moreover, if a family member is unable to visit during those limited three days when book delivery is permitted, the prisoner will have to wait an entire month before their family has another opportunity to send books again.

Accessing a novel series may require months of delay

There are also restrictions regarding the types and quantities of books allowed. In addition to requiring that books contain no content deemed as “incitement” — based on the discretion of prison officials — entertainment books such as novels are also limited. Specifically, if the book is part of a series, the entire series cannot be delivered into the prison at once.

Prisons also strictly enforce the rule that only one book may be delivered per month. Therefore, if a novel consists of multiple volumes, the prisoner may have to wait four to five months — or even longer — before being able to read the complete series. This is because it can take at least one month for a single book to reach the prisoner after being submitted.

Regardless of how many relatives are imprisoned, a family member is allowed to send only one book to one inmate per month.

The one-book-per-month limit becomes even more complicated when applied to visitors who are registered to visit multiple inmates. Even if they wish to deliver just one book to each person, the rules prohibit this. A single family member is only allowed to deliver one book per month, and only to one inmate, regardless of how many prisoners they are authorized to visit.

All of these rules governing book deliveries — and the practical consequences of such complexity — ultimately function more as restrictions rather than support for prisoners’ access to reading materials. They are at odds with the Department of Corrections’ stated intention to promote reading and expand the diversity of books available to prisoners.